Dublin Core

Title

Dominic Turillo - Echo Newspaper Article

Description

photo copy of a newspaper article

Type

Picture/Photo, Document

Format

Digital Image

Date

August 11, 1989

PDF Document Item Type Metadata

Transcription

Turillo Sheds light on Coastal Living

By Joe Fuoco, Echo Staff Writer

August 11, 1989

“I've seen a lot of ships go aground," he is saying. The view from the edge of the cliff is wide and magnificent. The haze is spreading. It's not fog yet, just a haze. In the far distance, near the horizon a large ship with its sails down is moving slowly, a smaller craft is bouncing in the surf. Domenic Turillo is putting on his glasses to see clearly.

"They move back and forth,” he says. “They sway. Years ago, when I was here all the time, it was nothing to get up in the morning and see small craft aground, even smashed, against the rocks."

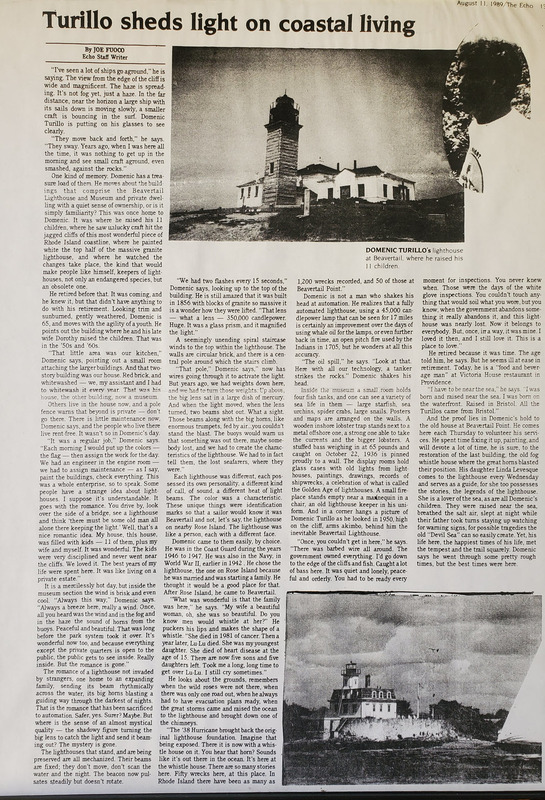

One kind of memory. Domenic has a treasure load of them. He moves about the buildings that comprise the Beavertail Lighthouse and Museum and private dwelling with a quiet sense of ownership, or is it simply familiarity? This was once home to Domenic. It was where he raised his 11 children, where he saw unlucky craft hit the jagged cliffs of this most wonderful piece of Rhode Island coastline, where he painted white the top half of the massive granite lighthouse, and where he watched the changes take place, the kind that would make people like himself, keepers of lighthouses, not only an endangered species, but an obsolete one.

He retired before that. It was coming, and he knew it, but that didn't have anything to do with his retirement. Looking trim and sunburned, gently weathered, Domenic is 65, and moves with the agility of a youth. He points out the building where he and his late wife Dorothy raised the children. That was in the '50s and '60s.

"That little area was our kitchen," Domenic says, pointing out a small room attaching the larger buildings. And that two story building was our house. Red brick, and whitewashed — we, my assistant and I had to whitewash it every year. That was his house, the other building, now a museum.

Others live in the house now, and a pole fence warns that beyond is private — don't go there. There is little maintenance now, Domenic says, and the people who live there live rent-free. It wasn't so in Domenic's day.

“It was a regular job,” Domenic says. “Each morning I would put up the colors — the flag — then assign the work for the day. We had an engineer in the engine room — we had to assign maintenance – as I say, paint the buildings, check everything. This was a whole enterprise, so to speak. Some people have a strange idea about lighthouses. I suppose it's understandable. It goes with the romance. You drive by, look over the side of a bridge, see a lighthouse and think there must be some old man all alone there keeping the light.' Well, that's a nice romantic idea. My house, this house, was filled with kids – 11 of them, plus my wife and myself. It was wonderful. The kids were very disciplined and never went near the cliffs. We loved it. The best years of my life were spent here. It was like living on a private estate."

It is a mercilessly hot day, but inside the museum section the wind is brisk and even cool. “Always this way,” Domenic says. “Always a breeze here, really a wind. Once, all you heard was the wind and in the fog and in the haze the sound of horns from the buoys. Peaceful and beautiful. That was long before the park system took it over. It's wonderful now too, and because everything except the private quarters is open to the public, the public gets to see inside. Really inside. But the romance is gone."

The romance of a lighthouse not invaded by strangers, one home to an expanding family, sending its beam rhythmically across the water, its big horns blasting a guiding way through the darkest of nights. That is the romance that has been sacrificed to automation. Safer, yes. Surer? Maybe. But where is the sense of an almost mystical quality — the shadowy figure turning the big lens to catch the light and send it beaming out? The mystery is gone.

The lighthouses that stand and are being preserved are all mechanized. Their beams are fixed; they don't move, don't scan the water and the night. The beacon now pulsates steadily but doesn't rotate.

"We had two flashes every 15 seconds," Domenic says, looking up to the top of the building. He is still amazed that it was built in 1856 with blocks of granite so massive it is a wonder how they were lifted. “That lens - what a lens – 350,000 candlepower. Huge. It was a glass prism, and it magnified the light."

A seemingly unending spiral staircase winds to the top within the lighthouse. The walls are circular brick, and there is a central pole around which the stairs climb.

“That pole,” Domenic says," now has wires going through it to activate the light. But years ago, we had weights down here, and we had to turn those weights. Up above, the big lens sat in a large dish of mercury. And when the light moved, when the lens turned, two beams shot out. What a sight. Those beams along with the big horns, like enormous trumpets, fed by air...you couldn't stand the blast. The buoys would warn us that something was out there, maybe somebody lost, and we had to create the characteristics of the lighthouse. We had to in fact tell them, the lost seafarers, where they were."

Each lighthouse was different, each possessed its own personality, a different kind of call, of sound, a different heat of light beams. The color was a characteristic. These unique things were identification marks so that a sailor would know it was Beavertail and not, let's say, the lighthouse on nearby Rose Island. The lighthouse was like a person, each with a different face.

Domenic came to them easily, by choice. He was in the Coast Guard during the years 1946 to 1947. He was also in the Navy, in World War II, earlier in 1942. He chose the lighthouse, the one on Rose Island because he was married and was starting a family. He thought it would be a good place for that. After Rose Island, he came to Beavertail.

"What was wonderful is that the family was here," he says. “My wife a beautiful woman, oh, she was so beautiful. Do you know men would whistle at her?" He puckers his lips and makes the shape of a whistle. "She died in 1981 of cancer. Then a year later, Lu-Lu died. She was my youngest daughter. She died of heart disease at the age of 15. There are now five sons and five daughters left. Took me a long, long time to get over Lu-Lu. I still cry sometimes."

He looks about the grounds, remembers when the wild roses were not there, when there was only one road out, when he always had to have evacuation plans ready, when the great storms came and raised the ocean to the lighthouse and brought down one of the chimneys.

"The '38 Hurricane brought back the original lighthouse foundation. Imagine that being exposed. There it is now with a whistle house on it. You hear that horn? Sounds like it's out there in the ocean. It's here at the whistle house. There are so many stories here. Fifty wrecks here, at this place. In Rhode Island there have been as many as 1,200 wrecks recorded, and 50 of those at Beavertail Point."

Domenic is not a man who shakes his head at automation. He realizes that a fully automated lighthouse, using a 45,000 candlepower lamp that can be seen for 17 miles is certainly an improvement over the days of using whale oil for the lamps, or even further back in time, an open pitch fire used by the Indians in 1705, but he wonders at all this accuracy.

"The oil spill," he says. "Look at that. Here with all our technology, a tanker strikes the rocks." Domenic shakes his head.

Inside the museum a small room holds four fish tanks, and one can see a variety of sea life in them — large starfish, sea urchins, spider crabs, large snails. Posters and maps are arranged on the walls. A wooden inshore lobster trap stands next to a metal offshore one, a strong one able to take the currents and the bigger lobsters. A stuffed bass weighing in at 65 pounds and caught on October 22, 1936, is pinned proudly to a wall. The display rooms hold glass cases with old lights from lighthouses, paintings, drawings, records of shipwrecks, a celebration of what is called the Golden Age of lighthouses. A small fireplace stands empty near a mannequin in a chair, an old lighthouse keeper in his uniform. And in a comer hangs a picture of Domenic Turillo as he looked in 1950, high on the cliff, arms akimbo, behind him the inevitable Beavertail Lighthouse.

"Once, you couldn't get in here," he says. "There was barbed wire all around. The government owned everything. I'd go down to the edge of the cliffs and fish. Caught a lot of bass here. It was quiet and lonely, peaceful and orderly. You had to be ready every moment for inspections. You never knew when. Those were the days of the white glove inspections. You couldn't touch anything that would soil what you wore, but you know, when the government abandons something it really abandons it, and this lighthouse was nearly lost. Now it belongs to everybody. But, once, in a way, it was mine. I loved it then, and I still love it. This is a place to love."

He retired because it was time. The age told him, he says. But he seems ill at ease in retirement. Today, he is a "food and beverage man" at Victoria House restaurant in Providence.

"I have to be near the sea," he says. "I was born and raised near the sea. I was born on the waterfront. Raised in Bristol. All the Turillos came from Bristol."

And the proof lies in Domenic's hold to the old house at Beavertail Point. He comes here each Thursday to volunteer his services. He spent time fixing it up, painting, and will devote a lot of time, he is sure, to the restoration of the last building, the old fog whistle house where the great hors blasted their position. His daughter Linda Levesque comes to the lighthouse every Wednesday and serves as a guide, for she too possesses the stories, the legends of the lighthouse. She is a lover of the sea, as are all Domenic's children. They were raised near the sea, breathed the salt air, slept at night while their father took turns staying up watching for warning signs, for possible tragedies the old “Devil Sea" can so easily create. Yet, his life here, the happiest times of his life, met the tempest and the trail squarely. Domenic says he went through some pretty rough times, but the best times were here.

By Joe Fuoco, Echo Staff Writer

August 11, 1989

“I've seen a lot of ships go aground," he is saying. The view from the edge of the cliff is wide and magnificent. The haze is spreading. It's not fog yet, just a haze. In the far distance, near the horizon a large ship with its sails down is moving slowly, a smaller craft is bouncing in the surf. Domenic Turillo is putting on his glasses to see clearly.

"They move back and forth,” he says. “They sway. Years ago, when I was here all the time, it was nothing to get up in the morning and see small craft aground, even smashed, against the rocks."

One kind of memory. Domenic has a treasure load of them. He moves about the buildings that comprise the Beavertail Lighthouse and Museum and private dwelling with a quiet sense of ownership, or is it simply familiarity? This was once home to Domenic. It was where he raised his 11 children, where he saw unlucky craft hit the jagged cliffs of this most wonderful piece of Rhode Island coastline, where he painted white the top half of the massive granite lighthouse, and where he watched the changes take place, the kind that would make people like himself, keepers of lighthouses, not only an endangered species, but an obsolete one.

He retired before that. It was coming, and he knew it, but that didn't have anything to do with his retirement. Looking trim and sunburned, gently weathered, Domenic is 65, and moves with the agility of a youth. He points out the building where he and his late wife Dorothy raised the children. That was in the '50s and '60s.

"That little area was our kitchen," Domenic says, pointing out a small room attaching the larger buildings. And that two story building was our house. Red brick, and whitewashed — we, my assistant and I had to whitewash it every year. That was his house, the other building, now a museum.

Others live in the house now, and a pole fence warns that beyond is private — don't go there. There is little maintenance now, Domenic says, and the people who live there live rent-free. It wasn't so in Domenic's day.

“It was a regular job,” Domenic says. “Each morning I would put up the colors — the flag — then assign the work for the day. We had an engineer in the engine room — we had to assign maintenance – as I say, paint the buildings, check everything. This was a whole enterprise, so to speak. Some people have a strange idea about lighthouses. I suppose it's understandable. It goes with the romance. You drive by, look over the side of a bridge, see a lighthouse and think there must be some old man all alone there keeping the light.' Well, that's a nice romantic idea. My house, this house, was filled with kids – 11 of them, plus my wife and myself. It was wonderful. The kids were very disciplined and never went near the cliffs. We loved it. The best years of my life were spent here. It was like living on a private estate."

It is a mercilessly hot day, but inside the museum section the wind is brisk and even cool. “Always this way,” Domenic says. “Always a breeze here, really a wind. Once, all you heard was the wind and in the fog and in the haze the sound of horns from the buoys. Peaceful and beautiful. That was long before the park system took it over. It's wonderful now too, and because everything except the private quarters is open to the public, the public gets to see inside. Really inside. But the romance is gone."

The romance of a lighthouse not invaded by strangers, one home to an expanding family, sending its beam rhythmically across the water, its big horns blasting a guiding way through the darkest of nights. That is the romance that has been sacrificed to automation. Safer, yes. Surer? Maybe. But where is the sense of an almost mystical quality — the shadowy figure turning the big lens to catch the light and send it beaming out? The mystery is gone.

The lighthouses that stand and are being preserved are all mechanized. Their beams are fixed; they don't move, don't scan the water and the night. The beacon now pulsates steadily but doesn't rotate.

"We had two flashes every 15 seconds," Domenic says, looking up to the top of the building. He is still amazed that it was built in 1856 with blocks of granite so massive it is a wonder how they were lifted. “That lens - what a lens – 350,000 candlepower. Huge. It was a glass prism, and it magnified the light."

A seemingly unending spiral staircase winds to the top within the lighthouse. The walls are circular brick, and there is a central pole around which the stairs climb.

“That pole,” Domenic says," now has wires going through it to activate the light. But years ago, we had weights down here, and we had to turn those weights. Up above, the big lens sat in a large dish of mercury. And when the light moved, when the lens turned, two beams shot out. What a sight. Those beams along with the big horns, like enormous trumpets, fed by air...you couldn't stand the blast. The buoys would warn us that something was out there, maybe somebody lost, and we had to create the characteristics of the lighthouse. We had to in fact tell them, the lost seafarers, where they were."

Each lighthouse was different, each possessed its own personality, a different kind of call, of sound, a different heat of light beams. The color was a characteristic. These unique things were identification marks so that a sailor would know it was Beavertail and not, let's say, the lighthouse on nearby Rose Island. The lighthouse was like a person, each with a different face.

Domenic came to them easily, by choice. He was in the Coast Guard during the years 1946 to 1947. He was also in the Navy, in World War II, earlier in 1942. He chose the lighthouse, the one on Rose Island because he was married and was starting a family. He thought it would be a good place for that. After Rose Island, he came to Beavertail.

"What was wonderful is that the family was here," he says. “My wife a beautiful woman, oh, she was so beautiful. Do you know men would whistle at her?" He puckers his lips and makes the shape of a whistle. "She died in 1981 of cancer. Then a year later, Lu-Lu died. She was my youngest daughter. She died of heart disease at the age of 15. There are now five sons and five daughters left. Took me a long, long time to get over Lu-Lu. I still cry sometimes."

He looks about the grounds, remembers when the wild roses were not there, when there was only one road out, when he always had to have evacuation plans ready, when the great storms came and raised the ocean to the lighthouse and brought down one of the chimneys.

"The '38 Hurricane brought back the original lighthouse foundation. Imagine that being exposed. There it is now with a whistle house on it. You hear that horn? Sounds like it's out there in the ocean. It's here at the whistle house. There are so many stories here. Fifty wrecks here, at this place. In Rhode Island there have been as many as 1,200 wrecks recorded, and 50 of those at Beavertail Point."

Domenic is not a man who shakes his head at automation. He realizes that a fully automated lighthouse, using a 45,000 candlepower lamp that can be seen for 17 miles is certainly an improvement over the days of using whale oil for the lamps, or even further back in time, an open pitch fire used by the Indians in 1705, but he wonders at all this accuracy.

"The oil spill," he says. "Look at that. Here with all our technology, a tanker strikes the rocks." Domenic shakes his head.

Inside the museum a small room holds four fish tanks, and one can see a variety of sea life in them — large starfish, sea urchins, spider crabs, large snails. Posters and maps are arranged on the walls. A wooden inshore lobster trap stands next to a metal offshore one, a strong one able to take the currents and the bigger lobsters. A stuffed bass weighing in at 65 pounds and caught on October 22, 1936, is pinned proudly to a wall. The display rooms hold glass cases with old lights from lighthouses, paintings, drawings, records of shipwrecks, a celebration of what is called the Golden Age of lighthouses. A small fireplace stands empty near a mannequin in a chair, an old lighthouse keeper in his uniform. And in a comer hangs a picture of Domenic Turillo as he looked in 1950, high on the cliff, arms akimbo, behind him the inevitable Beavertail Lighthouse.

"Once, you couldn't get in here," he says. "There was barbed wire all around. The government owned everything. I'd go down to the edge of the cliffs and fish. Caught a lot of bass here. It was quiet and lonely, peaceful and orderly. You had to be ready every moment for inspections. You never knew when. Those were the days of the white glove inspections. You couldn't touch anything that would soil what you wore, but you know, when the government abandons something it really abandons it, and this lighthouse was nearly lost. Now it belongs to everybody. But, once, in a way, it was mine. I loved it then, and I still love it. This is a place to love."

He retired because it was time. The age told him, he says. But he seems ill at ease in retirement. Today, he is a "food and beverage man" at Victoria House restaurant in Providence.

"I have to be near the sea," he says. "I was born and raised near the sea. I was born on the waterfront. Raised in Bristol. All the Turillos came from Bristol."

And the proof lies in Domenic's hold to the old house at Beavertail Point. He comes here each Thursday to volunteer his services. He spent time fixing it up, painting, and will devote a lot of time, he is sure, to the restoration of the last building, the old fog whistle house where the great hors blasted their position. His daughter Linda Levesque comes to the lighthouse every Wednesday and serves as a guide, for she too possesses the stories, the legends of the lighthouse. She is a lover of the sea, as are all Domenic's children. They were raised near the sea, breathed the salt air, slept at night while their father took turns staying up watching for warning signs, for possible tragedies the old “Devil Sea" can so easily create. Yet, his life here, the happiest times of his life, met the tempest and the trail squarely. Domenic says he went through some pretty rough times, but the best times were here.